Dongming Lu, engineer, UltraTech Co. Ltd.

UVplays an important part in China’s municipal wastewater disinfection. In China, 9,213 municipal wastewater (MWW) treatment facilities were built – treating a total of 227 million m3 of municipal wastewater every day (~60 BGD) up to the end of 2019 – while about 3,000 of these facilities used UV to disinfect a total of 162 million m3 of effluent daily (42.8 BGD). Although UV is used only by approximately one third of China’s MWW treatment facilities for disinfection, the volume of wastewater disinfected with UV is about 71% of China’s municipal wastewater treated. This means much more than half of China’s population benefit from UV disinfection.

Nevertheless, it shouldn’t be taken for granted that UV was the favored process in China. China’s MWW treatment facilities were not required by regulation to disinfect effluent until 2003, when outbreak of SARS took place.

Although a few MWW facilities in China voluntarily had disinfection as a last step of sewage treatment before 2003, these facilities used chlorination for disinfection. The present author conducted a UV survey and visited a dozen well-known Chinese wastewater treatment academics and senior managers of municipal drainage departments across China in 1999. None of them had heard UV could be used for municipal water disinfection at that time. Some of them had the perception that UV was good only for low-flow nonmunicipal applications.

Interestingly, a few international UV manufacturers started to enter China more seriously from 1999 to

2000, looking for opportunities that the giant country might offer. They ran into challenges, as many MWW treatment facilities at that time did not disinfect effluent. Even for those that did disinfect, the facilities had no confidence in UV, since there were no municipal UV references in China at the time. It took several years of strenuous effort by these manufacturers and their local Chinese partners to educate and promote UV disinfection in China, working with academics, professionals and government to promote the necessity of disinfecting municipal sewage. The benefits of UV disinfection and advancement of UV disinfection technology in Europe helped raise China’s awareness of the technology and its progress. These international players soon were joined by some local Chinese players, who quickly recognized potential benefits that UV disinfection could offer over chlorination. They started to develop Chinese-made UV systems.

Most people were reluctant to adopt a new technology in municipal applications, even though they did not quite like chlorination, and many MWW treatment facilities did not have to disinfect at the time. However, there were always a few forward-thinking Chinese design engineers and water works managers who were willing to embrace and try out new and better solutions. Eventually the first MWW UV disinfection system was installed in Shanghai in 2001, with the second in Wuxi in 2002. Then came the outbreak of SARS in 2003, which prompted the Chinese central government to mandate all MWW treatment facilities to disinfect their effluent. This led to a boom of UV demand in China.

Issues, challenges and solutions

The booming of the MWW UV market drew a lot of players to join the feeding frenzy. At one point, there were more than a dozen local Chinese UV manufacturers, as well as international players. Many Chinese UV manufacturers had no UV experience or expertise. They simply reverse-engineered imported UV systems – only at one-third to half the price of the imported systems – and many of these Chinese players even thought that UV was just as simple as putting lamps in water. At the same time, many Chinese customers and design engineers had little knowledge, or did not have appropriate knowledge, of UV technology. They needed to implement UV facilities quickly. Proper education on how to utilize UV disinfection across China in a timely fashion was almost impossible.

On top on this, China’s bidding rules favored the lowest priced systems. This resulted in a large portion of undersized UV systems implemented at some MWW facilities, which did not perform. This hurt the reputation of UV technology as a whole and negatively impacted some customers and engineers’ confidence in UV. A well-known Chinese engineer even wrote an article calling for the UV disinfection industry to be “disinfected.” In some regions of China, such as Jiangsu province and Xi’an city, UV disinfection is literally no longer in the race for MWW disinfection due to the many UV installations in those regions that did not perform well. Some facilities added chlorine after UV, and some switched from UV back to chlorine.

After almost 20 years of using UV for municipal wastewater disinfection in China, waterworks professionals and design engineers have better knowledge of UV players. As installed UV systems have been telling their own stories, the UV industry in China has been reshuffling. Nevertheless, the fundamental issues and challenges remain, i.e. how a customer and engineer could evaluate various UV proposals and compare apples to apples so that a properly sized UV system would be put in place and perform to meet regulated discharge limits.

Although China’s Ministry of Construction (MOC) set up an equipment standard for municipal UV disinfection systems (GB/T 19837-2005) in 2005 and called for bioassay dose sizing and validation approaches as a golden rule for UV reactor sizing, the standard is not enforceable. First, the standard is not mandatory, but rather a sort of guideline. Secondly, there are no government agencies and/or independent third-parties in China that can do the bioassay validation of UV systems. On top on this, the integrity of UV players has been under scrutiny in China. Some players, locals and internationals alike, use forged credentials/evidence, fake numbers and false claims in their bids. The game has not changed much in that regard.

Having said this, in retrospect, it seemed that players who did understand UV disinfection technologies – who could wisely balance between meeting customer needs and business desire, and who were able to demonstrate integrity – benefitted in the long run, in terms of brand reputation and market share. Recently, some promising work is being done. Two influential Chinese research institutions are establishing independent bioassay validation facilities and practices for UV systems. MOC revision of its 2005 UV equipment standard, which added bioassay dose validation protocol, came into effect in 2019. Again, it is not mandatory but is a good official educational reference. Another positive move is that the Chinese central government has been pondering its old bid rules and practices, as it appears that picking the lowest priced systems most likely would result in an engineering project with poor quality. This created a situation where everyone would lose: the customer, the vendor and the industry.

Municipal drinking water applications

The Chinese central government published a new national drinking water quality standard (GB5749-2006) in 2006, which was to become effective on July 1, 2007, with a grace period through July 1, 2012. The new standard comprises 106 water quality indicators, compared against 35 indicators in the old standard (GB5749-85). The new standard is certainly more stringent than the previous one, and adds Giardia and Crypto indicators into the sanitation section of the standard. The standard is mandatory.

However, the Giardia and Crypto regulation was very weak, as a municipal drinking water treatment facility would only be required to test and check for Giardia and Crypto once or twice a year. The chances of catching Giardia and/or Crypto in one or two samplings a year at an MWW facility is probably very slim. Many cities in China do not even have capabilities of testing Giardia and Crypto, so many MWW managers opt to turn a blind eye, claiming that they do not have Giardia and Crypto, though Crypto cases reported by academic investigation across the country are broad. Hence, it was not surprising that the new standard did not create a huge demand for UV systems outright.

In addition, municipal drinking water facilities managers and professionals tend to play it safe when adopting something new, which is a double-edged sword. The downside is that it would be hard to convince them to use UV. The positive side is that, if they want to use UV, they will pick up a good UV system that would work and perform at a premium. On the contrary, many of their MWW counterparts would not take UV or disinfection performance too seriously, as effluent will be discharged into receiving rivers, lakes and/or ocean. The mentality of some MWW facility managers is to let nature take care of the bugs. The good news is that Chinese government law enforcement for MWW monitoring has been tightening up in many places the past few years.

Nevertheless, the new drinking water quality standard opened people’s minds regarding drinking water safety and helped some engineers and professionals put drinking water safety in perspective.

In the meantime, a few UV manufacturers have been working strenuously in cultivating UV demand for MWW applications, and, again, there were a few forward-thinking engineers and facilities managers who realized that a multi-barrier disinfection strategy might be their best bet to ensure a safe drinking water supply.

They were willing to try out UV and work with UV manufacturers to better protect the public. There are now roughly 50 Chinese MWW facilities using UV as a primary barrier to disinfect over 10 million m3 of drinking water per day (2.6 BGD +) with chlorination to meet the regulatory residual chlorine requirement at the end of distribution lines.

Fifty is still a small portion, considering there are more than 10,000 MWW treatment facilities out there. There is still a long way to go, but the ball is rolling. More MWW UV projects are under design now, thanks to those who are forward-thinking.

As UV makes inroads in China’s MWW segment, a few UV manufacturers also have been working with academics. Investigations by Chinese water academics and observations by some MWW facilities operators also found various chlorine resistant microbes other than Giardia and Crypto in municipal drinking water supplies from south to north of China.

Many of these microbes are potential pathogens or conditional pathogens. MWW facilities and engineers were not aware of these microbes in the water, as they were not required by regulation to test for the microbes. It is impossible to test for all microbes in drinking water, either from a technical or cost perspective.

What should be of concern is that the long-term effect on human health of these potential pathogens in drinking water is unknown, although they do not seem to cause acute health problems. Therefore, it is easy for such microbes to slip through human scrutiny. The take-away message is that an MWW facility should provide the most robust barrier or barriers available against all microbes that could exist in a municipal drinking water supply, either known or unknown, tested or (more likely) untested.

UV AOP applications

Many of China’s existing MWW facilities and new facilities under construction have been implementing advanced treatment, such as oxidation processes, to meet the new drinking water standard. Source water for many of China’s MWW facilities is contaminated due to pollution. Ozone plus activated carbon is almost the gold standard oxidation process used across China. However, due to bromate concern in some parts of China and limitation of O3+AC process to meet more stringent taste and odor compound regulation in some regions of China, water professionals and engineers also have been looking for alternatives. This opens the door for UV AOP solutions.

Three MWW facilities in China installed the first UV AOP units in 2019, while more MWW UV AOP projects are in design. In fact, two large MWW facilities treating total flow of 365,000 m3/d (or 96 MGD) will purchase UV AOP systems for 2-Methylisoborneol (MIB) reduction in 2020. Chinese design engineers have a legitimate need to learn more about UV AOP processes and how to design and specify such a process as well as a UV AOP system. In the meantime, a Chinese research institution is working on drafting China’s UV AOP process design guidance manual to address such needs. International collaboration is needed. Like UV for municipal drinking water disinfection, much work is needed to convince Chinese design engineers and waterworks professionals that UV AOP is a viable treatment solution and to educate them on how to design and specify a UV AOP process independently.

UV research in China

Although UV may seem to be a niche technology, it comes as a surprise that a lot of UV-related research and investigations have been conducted in China. To a certain degree, this is attributed to the fact that UV is widely accepted for municipal water, in particular for municipal wastewater disinfection, in China.

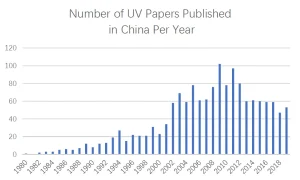

Data of Chart 1 is drawn from China Knowledge Net, a web-based literature resources site. It can be seen from the chart that the amount of Chinese UV-related literature published per year surged by great leaps roughly after 1999 and reached to a peak of 102 UV papers published in 2009 alone. Although the data in the chart also included UV air disinfection, the surge was attributed to municipal water disinfection – wastewater first, followed by UV AOP research, as well as drinking water disinfection. The literature ranges from fundamental research of UV inactivation efficacy of microbials to UV reactor design and sizing, bioassay validation, UV sensor and monitoring technologies, applications and engineering, and post-mortem assessment of UV system performance and operation. It is an excellent example of how the UV industry has grown and the public benefit from UV-related research and education. Academics are always there to respond to calls for problem-solving. It is encouraging to see a large community of academics and professionals who are interested in UV solutions in China.

Moving forward

After 20 years of fostering UV water purification technologies in China’s municipal water facilities, UV has established deep roots. It is no longer a stranger to most of China’s water design engineers and professionals, as it was some 20 years ago.

However, there is still much to be done to help Chinese design engineers and water professionals to understand how a UV system is sized and to present solid value propositions for it to be widely adopted to MWW and UV AOP applications – the key to future success and growth of China’s UV industry. This requires vision, dedication, commitment of resources and international interaction with China.